Mangroves, Manatees, and Scientific Monitoring in Belize

- Heather McKee

- Jul 8, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 9, 2023

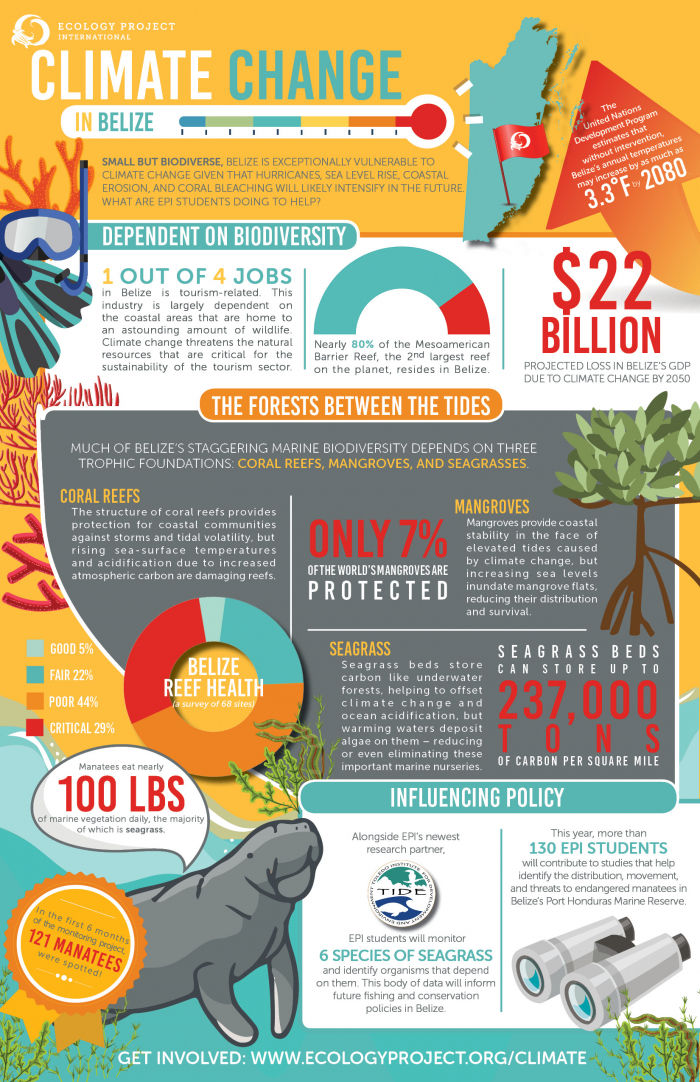

Belize’s coastal ecosystems are deeply diverse. From thrumming inland rainforests to dense processions of mangroves, rich seagrass beds, and expansive coral reefs, Belize buzzes with life. These unique ecological communities form the backbone of Belize’s environmental health, and Ecology Project International (EPI) students work with local conservation organizations to protect them.

The Mesoamerican Reef system in Belize is second in size only to the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. Its giant coralline structure has protected the Belizean coastline and communities for eons from the tempestuousness of the sea. The reef itself has historically been protected from inland and coastal pollution by an expansive filtration system—mangrove forests.

Mangroves are incredible examples of evolution. One of the only types of trees that can thrive in partial seawater submersion, mangroves survive by perching above their submerged anchor roots. They also have evolved complex methods to get rid of salt: either excreting salt from their leaves (see picture below), or by excluding salt in the first place via their taproots. They also grow knobby aerial roots stretching above the water to collect oxygen. Millions of these toe-like roots provide structural support for Belize’s coastlines, trapping and filtering sediments and preventing erosion.

The dense growth habit of mangroves also provides breeding and nesting havens for many types of birds in Belize: anhingas, neotropical cormorants, brown boobies, white ibis, a multitude of herons and others. Large populations of lobsters and crabs lurk in the mangrove’s shadows, and more than 70 species of fish feed and spawn in the mangroves, providing the basis for marine ecosystems and local human communities’ diets.

The diet of a growing global human population threatens these important forests. Shrimp farms, sugar cane plantations, and coastal development have all contributed to the destruction of 35% of the world’s mangroves in the past 40 years. Rising ocean levels due to climate change also place the mangrove in peril, as complete inundation can overwhelm the forests’ ability to filter seawater.

One well-loved marine mammal that browses its way through the mangrove channels, and the nearby seagrass beds, is the manatee. Belize is home to the critically endangered Antillean manatee. Due to habitat destruction, entanglement in fishing gear, and boat collisions, scientists believe there are only 2,500 Antillean manatees left in the wild.

The marine reserves in Belize are sanctuaries for some of these manatees. Each day, a manatee may eat up to 100 lbs. of vegetation, mostly seagrass. Seagrass beds are also carbon sinks, with deep and rich carbon sequestration occurring beneath their roots. Rising water temperatures encourage algae growth, however, which can smother seagrass beds and take away important feeding, breeding, and calving grounds for the manatee.

Our newest partner, the Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE), is a local organization managing some of Belize’s wildest and most diverse protected areas. In 2019, over 130 EPI Belize Marine Ecology students will work with TIDE to monitor manatee populations in the Port Honduras Marine Reserve, recording observations as the whiskered manatees rise to the surface for breaths of air.

Students will also conduct snorkel surveys to analyze the flowing seagrass beds in the reserve, tracking cover, height, species diversity, and abundance. Students will also record the species that feed and live in the seagrass, including commercially important conch, lobsters, and fish. TIDE will utilize this critical data to make policy recommendations for future fishing and conservation.

EPI’s programs are not just about the data, though. By immersing students in authentic conservation research, we give them the opportunity to recognize the scientists within themselves. Their experience empowers them to see that they are capable of making a difference in the world. More than 70% of our field science programs are conducted with local students living near or in these incredible sites through the Americas. EPI offers visiting students opportunities for cultural exchange, and a chance to learn from and alongside local residents working to protect their own homes and environments.

In connecting them to field researchers, EPI hopes to spark a passion for conservation in each of our students. Beyond our courses, we hope they will become local and global conservation leaders, finding solutions to the biggest and most pressing environmental challenges of our day. If you’d like to learn more about opportunities to join EPI in the field, get in touch today!